1.0 Preparation & Training

1.0 Preparation & Training

HOW TO APPROACH PHYSICAL

CONDITIONING

The capacity for, and

tolerance to, physical exertion varies from person to person. It is therefore

important to approach training in a way which gradually increases this tolerance

without undue strain, exhaustion, or persistent muscle soreness. You are not

overdoing it if at the end of each session you are feeling pleasantly tired but

not fatigued. Any muscle soreness should not continue beyond the second day.

Here a psychological factor comes into play: the more you overdo it, the easier

it is to get discouraged. Slow down when necessary, but do not give up. No real

ability of any kind can be achieved without sustained effort. Depending on

age and physical condition, you should train two to three times a week. Results

are hard to achieve with less training, at least until such time as your

reflexes have received a minimal conditioning. Claims to the contrary are not to

be taken seriously. Naturally, if you aim to become a champion, you should

devote to training as many of your waking hours as you can.

Stamina, related to cardiovascular efficiency, and understood as the ability of

the organism to utilize oxygen efficiently, is perhaps the most important

attribute of physical fitness. It can be developed very effectively through

jogging, which you may do with a dual purpose, putting your hands to good use.

The sliding hands exercise, employing the stick, is very useful in this respect

(see p. 27). Then, as you jog, you may perform alternatively left and right

circular spring-slashes (see p. 40).

Finally, you may strengthen your grip as you jog either by using commercially

available grip spring-tensors, or by squeezing a couple of small rubber balls.

In either case, try to make a conscious effort to use your little finger

efficiently when squeezing. A strong, flexible, and sensitive grip is an

important requirement for developing and directing power effectively. The

following sports have a beneficial effect on stickfighting: skiing, sprinting,

broad jump, high jump, soccer, dancing (for strong legs and a good sense of

rhythm and timing), and last, but not least, training appropriate to kickboxing.

DEVELOPING POWERFUL SLASHES AND THRUSTS

It is a fallacy to believe that the ability to deliver powerful blows, slashes,

and thrusts is meaningful without first developing accuracy, timing, and good

balance, not only during delivery, but also during the recovery that follows.

Failure to realize this invariably results in lack of mobility and a stilted

style. Power is of the utmost importance, but only in its proper place.

Developing and conditioning the muscles is only part of their preparation for

actual combat.

As earlier mentioned, power is developed through the use of the principles of

momentum and leverage. The very use of our bodies implies leverage and it is not

necessary to belabor the point. The use of momentum, however, needs some

clarification. Momentum is closely related to speed and mass. Acceleration

means that the momentum of the attack steadily increases as the blow progresses

toward its target. The kinetic energy thus developed will be most effective if

it is transferred as completely as possible to the target at the point of

impact. This involves mental as well as physical concentration. Keep the two

following points in mind.

l. The smaller the area of impact, the more destructive the result will be,

because it will mean more force per square inch.

2. The less dissipation of power (i.e., kinetic energy) through cushioning from

the joints involved, the better its transfer to the target, hence the necessity

for completely tensing the attacking limb, as well as the body, at the moment of

impact.

Complete exhalation at

that moment is helpful because it tightens the large muscles of the midsection.

The concentration of resources described above is called "focus." To allow the

shock waves generated by the impact to propagate through the target, one should

instantly withdraw the attacking limb on impact. Instant relaxation of the

muscles involved helps to achieve this speedy withdrawal. Thus, as long as

the various parts of the body involved in delivering a blow abide by these

principles, such an attack will be destructive, assuming it is accurate. This

explains how boxers, kickboxers, and those who practice karate can deliver very

powerful blows. It follows that any powerful technique must of necessity start

with as little tension as possible in the attacking limb, then develop momentum

by smooth coordination of the parts of the body involved and, finally, culminate

in full tension at the point of impact. In summary, then, the smaller the area

in which the kinetic energy developed is transferred, the more destructive the

attack. The more tense the attacking limb at the point of impact, the less give

it will have and the more penetrating the attack will be. Of course, training in

the A.S.P. system is consistent with the foregoing, though we aim at developing

balance, accuracy, and then power, in that order.

WRIST CALISTHENICS

In A.S.P. we have special calisthenics aimed at developing strength,

flexibility, and power in wrist action (a quality most important in

stickfighting). In the sport of sabre fencing as well as in stickfencing (not

fighting) it is not desirable to use powerful blows, because the purpose is not

to hurt the opponent, but to touch him in order to score. Indeed, only poor

fencers slash and thrust with force. Besides losing speed of action, fencers

using force soon find out that their partners take a rather dim view of such a

habit. In stickfighting, on the contrary, one must develop powerful parries,

slashes, and thrusts in order to foil real attacks and incapacitate an opponent.

It follows, then, that while a fast action is desirable both in fencing and

stickfighting, a strong wrist action is considerably more important in the

latter. The main topic of this book is stickfighting for self-protection and it

will, naturally, receive most attention. However, the sport of stickfencing can

play a very valuable role in training, and so Chapter 5 of this book is devoted

to it. The sport is best approached after the student has become acquainted with

the fundamentals of stickfighting. On the following page is a selection of wrist

calisthenics to help prepare the student for training.

The Prayer. Put your palms against each other in a prayerlike fashion, wrists

and elbows at the height of the shoulders. You should feel a stretching of the

muscles of the wrist, and initially this may be somewhat uncomfortable. Then,

pointing the fingers in succession, upward, to the front and away from you,

downward, and then toward you, stretch then bend your arms in each position.

While doing this you will feel the stretching of the muscles of the wrist. Make

sure your palms are pressing well against each other. Repeat the sequence at

least ten times.

The Cross. Fold your arms on your chest as follows. Cradle your left hand in

your right arm with the inside of your right elbow between the thumb and index

fingers. The thumb is pointing down and the left wrist bends as you fold the

right forearm over the left, tucking the right hand beneath the left elbow.

Apply pressure on the bent left wrist by bringing the elbows closer to each

other and, when the pressure is at its maximum, lift the right elbow above the

left. This action twists the wrist upward on the side of the ulna (the forearm

bone opposite the thumb). This composite pressure strengthens the wrist and

renders it more flexible and less sensitive to pain. Repeat this exercise at

least ten times on each wrist. You may also achieve the same action on

each hand by pressing the back of one hand with the palm of the other in the

direction of the wrist and twisting it upward and toward you.

The Twist. Bend both wrists fully while standing, arms along the sides, and

rotate your wrists as completely as you can so that they describe two complete

circles, the right wrist rotating in an opposite direction to that of the left.

Repeat at least ten times.

The Seal. This exercise involves push-ups on the flexed wrists (palms facing

up), which are gradually rotated in opposite directions after each push-up. A

push-up is performed in each new position of the wrist, until as full a circle

as possible is completed. This is a difficult exercise initially, but perhaps it

is the best of all. If your wrists hurt too much, don't insist: stop. Work at it

gradually. If regular push-ups are too hard initially, start with push-ups which

leave the hips on the working area.

The Stab. Standing up,

bend your right wrist completely, fingers pointing down. Shoulders, elbows, and

wrists being in one plane, curl the left fingers, knuckles pointing up, and

bring both arms together with force, striking the right wrist against the heel

of the left palm. Repeat several times, but stop if your wrist hurts too much.

Repeat several times, switching wrists. This exercise strengthens the wrist

against impact.

EXERCISES WITH THE STICK

These exercises aim at familiarizing one with the handling of the stick.

Sliding Hands. Hold the stick diagonally across your chest with both hands, one

at chest level, and the other close to the opposite hip. The fingers of each

hand are held toward you. For example, if the right hand is held close to the

right breast, the left hand should be close to the left hip, and the upper tip

of the stick near to the right shoulder. Now, slide your hands together, then

over and away from each other (Fig. 1).

Pull outward as you slide your hands away from each other, to bring the upper

tip near to the left shoulder. Repeat, increasing the tempo until you are doing

it as fast as you can. Then try to increase the speed even more.

Horizontal Twirl. Grasp the stick at the middle with your right hand, extend the

right arm at shoulder height in front of you and twirl the stick using the

wrist, forearm, and fingers so that its tips describe two parallel and almost

horizontal circles. Increase speed as you become familiar with the exercise and

repeat with the left hand.

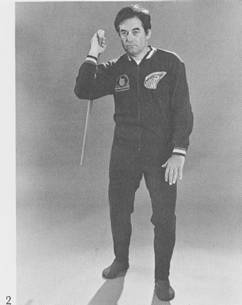

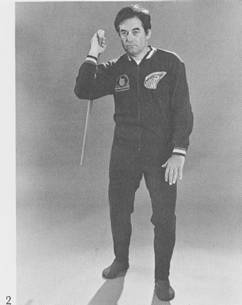

Vertical Twirl. Grasp the stick near one of its tips with your right hand and

point it up by bending the elbow, bringing up the forearm. Then, with a forward

motion of the elbow, let the far tip of the stick drop behind your right

shoulder (Fig. 2). Now swing it in a vertical circle parallel to your right

side, keeping your elbow bent by the side, and coordinating the forearm, wrist,

and fingers to give a smooth action. The palm of your right hand faces

alternately up and down. Practice with each hand, one after the other, and

increase the speed as you become more familiar with the exercise.

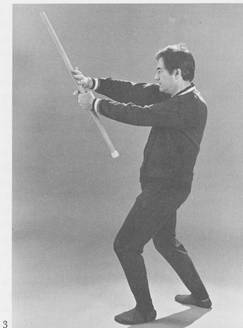

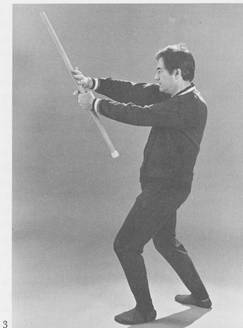

Changing Hands Twirl.

This exercise can only be properly performed if the length of the stick used is

correct. Grasp it at the middle with both hands, palms facing each other. Extend

your arms as much as possible. Now twirl the stick in a vertical plane in a

constant circular motion, bringing each tip of the stick up between your arms.

Do this by changing grip in such a way that each palm is alternately facing

toward you and away from you (Fig. 3). If done right, the stick will not bump

against your arms, body, or face.

HOW TO APPROACH TRAINING

The mental attitude with which training should be approached must combine

sportsmanship with detachment. One of the main difficulties in practicing a

combative art usefully is the need to attack realistically, but without hurting

one's partner. Unless an attack is meant, one cannot expect to practice the

defensive technique properly. Realistic attacks can be achieved by aiming

accurately at the target area, and by carrying the momentum of the attack

through without excess and with a certain degree of relaxation. If the evasive

technique is not successful, the momentum should be controlled so as to give

only a gentle contact. Realism in this context is largely dependent on accuracy

and speed, both of which can be achieved without brutality.

There is a great benefit in practicing on both sides, one side immediately after

the other. The tempo of the techniques should be slow initially, until their

elements have been mastered. Then the speed can be gradually increased. The

final touches are given with the help of free sparring, which is a necessary

part of any advanced training. In the context of free sparring, the attacker

desists from his attack as soon as it comes under the control of the defender

and its first impact is foiled. Cooperation among the participants is essential

and training should never become a pretext for a free-for-all fight. Light

contact in retaliatory techniques is recommended during training because,

besides developing the sense of distance, it teaches the attacker to control his

attack and also teaches both partners to accept a degree of punishment.

Controlling techniques such as locks and chokes must be practiced with even more

caution than the other techniques since they can be quite dangerous.

All this means that you have to practice conscientiously, and that it is to your

disadvantage to spread yourself too thinly over a large number of techniques. It

is much better to concentrate on a few versatile and efficacious ones which you

think are well suited to you and which you fully understand.

The

American Self Protection Association, Inc.

The

American Self Protection Association, Inc. 1.0 Preparation & Training

1.0 Preparation & Training